2023 DRU National Summit

Table of Contents

Topic 1: Increased Organizational Resilience through Innovative Facilities Management

Topic 2: National Intercollegiate Mutual Aid Agreement

Topic 3: Campus Partner Perspectives

Topic 4: Incident Management Teams - Not a One-Size-Fits-All Approach

Topic 5: Team Building

Topic 6: Crisis Communications Case Studies

Executive Summary

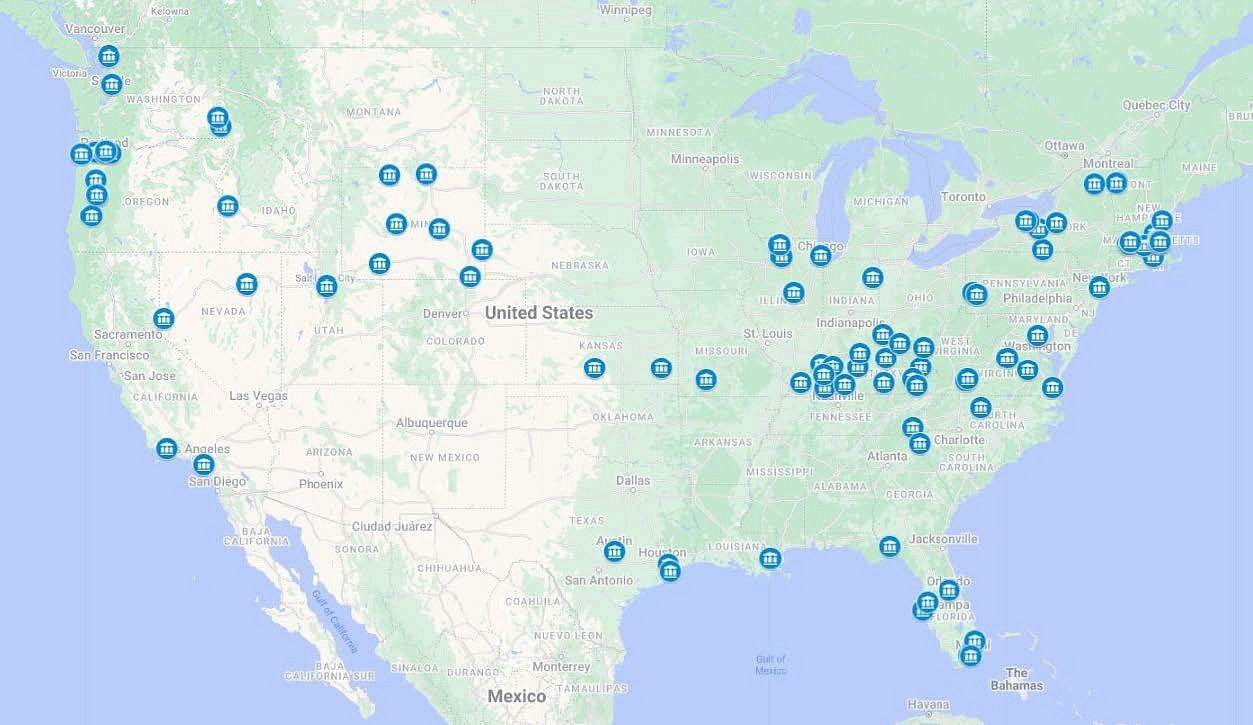

The DRU Network is an online platform for communication, coordination, and collaboration among more than 2000 members representing approximately 800 institutions of higher education (IHEs).

Its goals are to:

- Facilitate professional, peer-to-peer communication among members in order to help campuses mitigate, prepare for, respond to, operate during and recover from natural disasters, acts of terrorism, or other human-caused crises or disasters.

- Give post-secondary risk and safety administrators and practitioners ways to share research, studies, strategy documents, technical papers, process evaluations, and lessons learned.

The 2023 National DRU Summit furthers the DRU Network's mission. Held on April 18-20, 2023, at the University of Oregon in Eugene, Oregon, the Summit featured presentations by higher education experts and thought leaders,and peer-to-peer discussions, workgroups, and networking sessions. Attendees got a first look at the DRU Library, a digital collection of safety, risk, and resilience resources provided free by the DRU Network.

The Summit's 100+ participants from over 50 IHEs acquired new tools, resources, and ideas for making their campuses more disaster-resilient. A core theme at this year's summit was communication and its role at all levels from day-to-day operations to crisis response.

The 2023 National DRU Summit covered seven topical areas:

- Organizational resilience through facilities management

- Mechanics of the National Intercollegiate Mutual Aid Agreement (NIMAA)

- How Incident Management Teams (IMTs) work with campus partners

- Approaches to building and deploying IMTs

- Team-building via the DiSC Profile

- Crisis communications case studies

- Crisis communications best practices

Topic 1: Increased Organizational Resilience through Innovative Facilities Management

Emerging technologies are helping IHEs become more resilient. This session provided an overview of the University of Oregon's Location Innovation Lab and how its suite of custom software applications help support their campus operations, emergency management, planning, business continuity, and more.

Panelists

- Ken Kato - Director, Location Innovation Lab

University of Oregon (Moderator) - Jeff Butler - Director of Facilities Management

University of Oregon - LeAnna Pitts- Assistant Director, Work Management

University of Oregon - Ashley Dougherty - Assistant Director of Security Operations

University of Oregon - Zach Earl - Interim Fire Protection Manager

University of Oregon

Discussion

The Location Innovation Lab develops smart-city software applications, together with administrative units across campus, in the pursuit of fostering a more resilient organization. Partners from UO Facilities Services, Security Operations Center, and the Office of the Fire Martial joined the presentation to discuss the apps they've created, with a focus on the innovation process, not just the tools that resulted.

Demonstrated Applications

These location-based tools are tied to the campus map and address issues including workflow routing for service calls, asset management, incident management, and student food insecurity.

- UO Spaces - This space management system provides real-time room-level information for 29,000+ rooms to users across the organization.

- Call Log - This is a map-centric, room-level intake and management system for facilities maintenance, safety, security, and infrastructure service calls. Users request services by dropping pins on a digital campus map. The app has routed over 85,000 room-level calls for service and has nearly 1,000 users.

- Anvil - This iPad app connects trades workers and technicians performing at UO with the calls for services submitted through Call Log. This mobile tool is used when assessing and completing work in the field and integrates with UO Spaces.

- Orion - This is an incident management and internal communications platform for large-scale events. It has been used during natural disasters, Olympic Trials, World Athletics Championships, and football games. Orion provides a critical common operating picture for rapidly evolving incidents.

- Canary - This app polls user-selected air-quality monitoring stations in a region of interest via the EPA's AirNow system. A text message alerts users when the Air Quality Index (AQI) exceeds a specified threshold. Canary was developed to help efficiently manage the environmental health and safety regulations for employee exposure to wildfire smoke.

- Leftover Textover - Developed to address student food insecurity, this app texts students when there is leftover food available from catered campus events. Since its launch, Leftover Textover has sent more than 60,000 notifications to students.

Key Takeaways

- Culture eats strategy for breakfast. The innovation strategy we've found most successful leans heavily on creating a culture of creativity and staff engagement while leveraging existing resources and knowledge to foster trust-based partnerships. Our focus is on the process - the journey we embark on together - ahead of the technical methods we'll come up with to tackle the task.

- Buildings talk to us through people. Our apps rely on the people using our spaces on campus to act as our primary "smart sensors." We've logged nearly 100,000 room-level, real-time data points as requests for service that are rapidly routed to responding teams across campus. By empowering people with well-designed and easy-to-use apps, we know when water is dripping into a space faster than we do from expensive and hard-to-maintain sensors.

- Create situational awareness through a common operating picture. Putting quality, timely information in front of smart people not only provides operational efficiencies, but it also serves as the front line of incident management and resiliency. We've found that many "incidents" on campus start out as simple and easily solvable small issues that weren't detected, shared, or routed well, resulting in an outsized response. Our apps are designed to scale from a coffee spill to a hazardous materials spill.

Topic 2: National Intercollegiate Mutual Aid Agreement

This brief session presented an overview of the National Intercollegiate Mutual Aid Agreement (NIMAA), which provides a framework for colleges and universities to request resources from other campuses.

Presenter

Krista Dillon, Chief of Staff and Senior Director of Operations, Safety and Risk Services

University of Oregon

Discussion

Colleges and universities don't typically have enough personnel and/or resources to respond effectively to large-scale crises without outside support. Local governments may also be overwhelmed by a crisis and/or not have optimal resources for IHEs. Nonetheless, numerous disasters over the past 25 years show a need and opportunity for mutual aid to change outcomes.

Created in 2015, the NIMAA helps IHEs share personnel, teams, equipment and supplies locally, regionally, or nationally. IHEs can request help from other participating IHEs directly via phone, email, or text; they can also send a broadcast message to all IHEs via email or Basecamp. Help isn't only available on bad days; IHEs can also ask for help with tests or exercises.

Unlike typical government mutual aid agreements, NIMAA membership includes both public and private institutions. The NIMAA is complementary to other mutual aid agreements and programs; it works in cooperation with other plans.

NIMAA is a legal instrument that now has 117 signatory institutions.

Topic 3: Campus Partner Perspectives

This session gathered members of the University of Oregon's Incident Management Team (IMT) who work in areas outside of Safety and Risk Services. They shared their perspectives on when IHEs should activate their IMTs, what realistic expectations IHEs should have regarding the benefits of training, and what IHEs can do to get nonemergency personnel to join their IMTs.

Panelists

- Krista Dillon - Chief of Staff and Senior Director of Operations, Safety and Risk Services

University of Oregon (Moderator) - Kris Winter - Interim Vice President of Student Life

University of Oregon - Greg Shabram - Chief Procurement Officer

University of Oregon - Cass Moseley - Vice Provost for Academic Operations and Strategy

University of Oregon - Fred Sabb - Research Associate Professor, Assistant Vice President for Research Facilities

University of Oregon

Discussion

An IMT is a group of trained professionals from across campus who provide a command-and-control system to manage logistical, financial, informational, planning, safety, and other issues during the response, continuity and recovery phases of an emergency. Not all members of an IMT work in departments directly related to risk or emergency management.

Several of the panelists shared their perspectives on what participating on an IMT is like for them and why their participation is importation.

Key Takeaways

- Frequent meetings pay. Meeting often allows IMTs, and in turn IHEs, to solve big problems faster. Team members know each other better and can make faster decisions as a result.

- Diversity of skills is crucial. When subject matter experts join IMTs, they form a powerful network that allows for comprehensive and nuanced decision-making during emergencies.

- Networking opportunities are significant. ICS training gives participants access to people they normally don't have opportunities to interact with, as well as time to have frank and productive conversations with those people in a trusted space.

- Know who needs training and who doesn't. Some team members don't need all levels of ICS training. IHEs should think about how to train their policy groups so they understand what ICS training best serves the institution.

- Procurement and student affairs experts are good candidates for most IMTs. Procurers typically participate in incident responses regardless of IMT membership, though chief procurement officers are often Logistics Section Chiefs on IMTs. Additionally, student affairs professionals have expertise handling and navigating crises.

Topic 4: Incident Management Teams

Not a One-Size-Fits-All Approach

This session included panelists from a variety of IHEs. They provided details about how they structured their incident management teams (IMTs) or response teams and how often they activated those teams. The panel included campuses with traditional incident command system (ICS) structures, as well as those with emergency support functions and other options.

Panelists

- Krista Dillon - Chief of Staff and Senior Director of Operations, Safety and Risk Services

University of Oregon (Moderator) - Bill Curtis - Director of Emergency Management

Lewis and Clark College - Will Smith - Director, Georgia Tech Office of Emergency Management & Communications

Georgia Tech - Laurie Friedman - Deputy Emergency Manager

Stanford University

Discussion

There's more than one way to build an IMT, and many IHEs have developed IMT structures customized to their needs and resources. In this session, panelists described how their IMTs are structured. Their experiences with these structures offered several key takeaways for other IHEs.

Key Takeaways

Size can hinder IMTs. Small IHEs have fewer people to call upon in an emergency. The people they do call upon tend to have numerous job duties, which can make problem-solving more complex and prevent attendance at multiday ICS training, which can impede the IHE's resilience capabilities.

Activation thresholds aren't uniform. One IHE's IMT activates based on three response levels.

- Level 1, which is for situations that don't affect the campus or warrant actions from the emergency management team.

- Level 2, which is for situations affecting part of the campus but not warranting action from the emergency management team.

- Level 3, which is for situations that warrant action from the emergency management team.

Another IHE uses a Situational Triage and Assessment Team (STAT) staffed by the IHE's leaders from the communications, facilities, residential and dining, human resources, public safety, IT, environmental health and safety, student affairs, health and research teams. Key responders bring information to Zoom calls with STAT.

Team engagement is key. Participants recommended doing three things to give IMT members opportunities to practice emergency management principles.

- Meet at least monthly for tabletops or other reasons, using the technology the IMT would use in an actual activation. This helps members learn tools and methods ahead of time.

- Assign team members to participate in editing drafts of emergency operations plan (EOP) annexes. This helps members take ownership of and obtain more intimate knowledge of the IHE's emergency plans.

- Have team members write incident action plans (IAPs) for common events. Include the Emergency Operations Center (EOC) in the drafting process so team members understand what an IAP looks like and what happens if there is an EOC activation.

IMT structures aren't uniform. One IHE has 18 emergency support functions (ESFs) in its EOC, in part because many of the IHE's departments receive funding that requires operating dedicated maintenance teams.

Activation processes vary. One IHE uses Rave Mobile Safety to send emergency notifications to people with authority to activate the IHE's EOC. The notification directs recipients to an email detailing which people and departments are activated. Those activated then join a Zoom call lasting fewer than 30 minutes. The meeting has a set agenda focused on an ICS briefing chart detailing what happened, actions needed, and who will execute.

One IHE meets via Zoom or an Everbridge conference call. Although the IHE's STAT team joins the call and has decision-making authority, it often invites subject-matter experts to share information.

One IHE activates its EOC when there is a significant incident or threat, when there are multiple operational periods involved, and when coordination among multiple ESFs is needed. It activates its crisis management team (CMT) when needing to make policy decisions, and when it needs to brief executives.

Some IHEs are investing in backup or portable EOCs. Two IHEs reported that they only need a large conference room to set up a temporary EOC, largely due to investments in lighter portable EOC equipment and systems. One IHE said it is also building an earthquake-ready EOC. Of importance to primary EOC's is display space for viewing camera footage or other visual information.

IHE EOC's exercise. One IHE noted that exercises described as tabletop exercises tend to draw more participation, thus allowing its EOC to do larger, more frequent exercises. Another IHE said its EOC exercises about once per month and meets with the IHE's executive council about twice a year to talk about exercises.

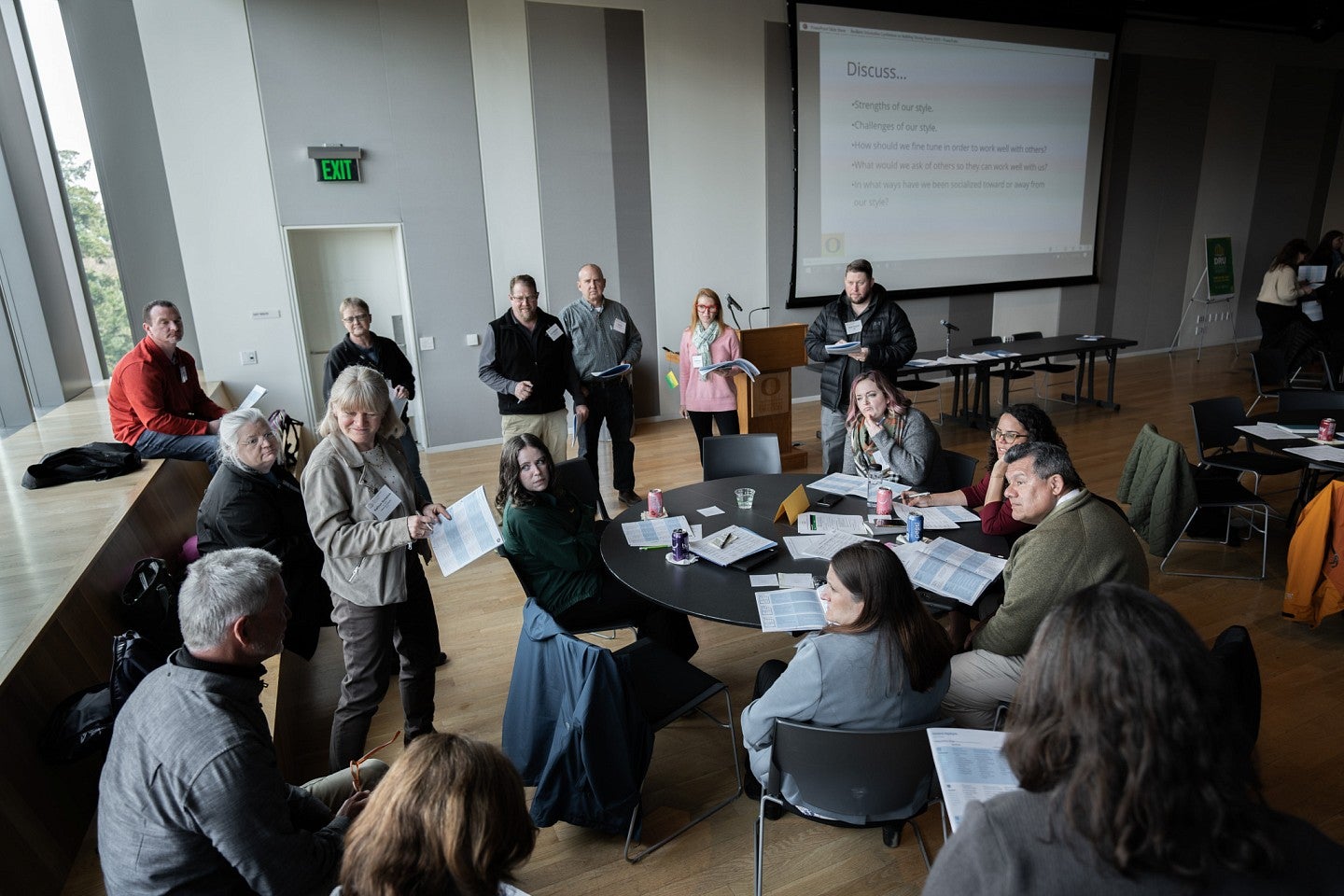

Topic 5: Team Building

This session included several best and promising practices to help IHEs build high-performing teams and build leadership skills on those teams. Participants took the DiSC Profile assessment, which is a personal assessment tool used by more than one million people every year to help improve teamwork, communications, and productivity in the workplace.

Panelists

Krista Dillon - Chief of Staff and Senior Director of Operations, Safety and Risk Services

University of Oregon

Jennifer Espinola - Law Dean of Students, Knight Law School

Director, Frohnmayer Leadership Program

University of Oregon

Topic 6: Crisis Communications Case Studies

This session included a panel discussion with communication leaders who shared how their IHEs responded to specific recent crises or critical issues.

Panelists

- Richie Hunter - Vice President, University Communications

University of Oregon (Moderator) - Kay Jarvis - Senior Director Media Relations and Issues Management, University Communications

University of Oregon - Jenny Petty - Chief Marketing Communications Officer

University of Montana - Phil Weiler - Vice President for Marketing and Communications

Washington State University

Discussion

The panelists provided detailed overviews of recent situations on and near their campuses involving active shooters, student deaths, and misconduct. Each case discussed details of the incident, walked through a timeline of the IHE's response, and shared what the IHE did and didn't do well in hindsight.

These case studies highlighted several key questions that IHE communications teams often have during incidents such as:

- What happens if a key team member is unreachable or not responding to messages?

- Can we embed communications personnel with responding officers?

- How much time and effort should we devote to monitoring news channels and social media?

- When there are multiple communications teams at an IHE, how do you determine which ones should be involved and when?

- How much weight does the communications team have in determining whether a campus should close?

- How long is it appropriate to wait to notify families of a student death before notifying the campus community?

- What happens if traditional or social media channels have more information about an incident than and IHE does?

Key Takeaways

- Designate backups. When team members don't respond to messages or calls, critical delays can occur in getting messages out to people. An on-call schedule can be critical in those situations.

- Different audiences often require different responses and talking points. For any given incident, residence hall students and families often have different information needs than do campus research operations, for example, or off-campus residents.

- Multiple messages are ok. IHE leaders may want to create, review, and approve long, complex messages during and after an event. Though thorough, this strategy can create conflicts and delays; communicating what the IHE knows as soon as it knows it is often better than "saving up" information. To increase agility, IHEs should agree on a short list of people who can review and approve messages.

- Monitor news and social media early on. One panelist said its monitoring efforts caught a local news team reporting incorrect facts while an incident was still in progress, which gave the IHE's communications team an opportunity to call the station and correct the reporting at a crucial time. One IHE noticed that details of a student's death were becoming widely available on social media before the IHE had released information, which led to tough questions about why the IHE wasn't sharing information. Monitoring social media during the event helped the team know what follow-up messaging was necessary.

Topic 7: Promising Practices in Crisis Communications

This session included a panel discussion with communications leaders who shared promising practices for crisis communications and issues management.

Panelists

- Richie Hunter - Vice President, University Communications

University of Oregon (Moderator) - Keith Frazee - Associate Vice President and Chief of Staff, University Communications

University of Oregon - Jennifer Winters - Associate Vice President Content Strategy, University Communications

University of Oregon - Jenny Petty - Chief Marketing Communications Officer

University of Montana - Phil Weiler - Vice President for Marketing and Communications

Washington State University

Discussion

Internal crisis communications plans help IHEs prepare employees and students for various situation, help mitigate or reduce crises, reduce misinformation and speed recovery, among other things. Panelists reviewed key, best-practices elements of crisis communications planning at IHEs.

Key Takeaways

- Identify the team ahead of time. Define in writing each person's roles, areas of responsibility, and backups.

- Map the audiences. Map the IHE's audiences by affiliation, location, and job type. Be sure the crisis communications plan incorporates deans, directors, and supervisors, as well as other communicators and influences.

- Map communications channels. Acknowledge the multiple methods of communication, some of which are well established. Remember to consider nondesk employees and how information reaches them.

- Establish policies and inform the campus. This means aligning on authorizations, providing timely reminders, and practicing with tactics and tools.

- Prepare templates and statements. These flexible, preapproved documents can dramatically reduce the amount of time needed to prepare various communications and can help ensure consistency in those communications.